Charlotte Durand is a PhD student working on data assimilation and deep learning as part of WP4. She is supervised by Marc Bocquet at the Atmospheric Environment Teaching and Research Center (CEREA) and works closely with Alberto Carassi, WP4 PI leader. She will soon receive her PhD and join the Institute of Environmental Geosciences to continue her work on SASIP alongside Pierre Rampal and the other members of the SASIP team based in Grenoble, France.

“SASIP is working on the development of a new sea ice model using various strategies, particularly the collaborative development of both the physical model and the machine learning approaches that complement it…I genuinely believe that bringing together people from different fields within this project allows everyone to grow from a scientific perspective.”

_An interview with Charlotte Durand.

By: Solène Guyard.

Monday, October 21, 2024.

Was a life in research something you always have envisioned for yourself?

Around the age of 14, in France, we have a mandatory small internship. I did mine in a pharmaceutical research lab. The conclusion of my report was clear: I would never do research! I still don’t know if I’ll spend my entire career in research, for a lot of reasons, but when it comes to education, I think it was the most natural choice for me.

What subject did you study during your thesis and what did your research aim at understanding in the context of SASIP?

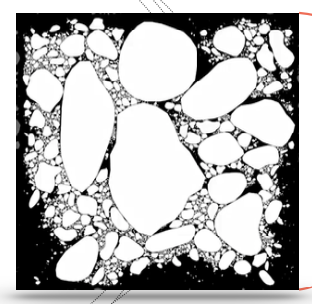

During my PhD, I explored the possibility of replacing a sea ice model, neXtSIM, with a neural network using deep learning. The basic idea is quite simple: use a neural network to learn the evolution of sea-ice thickness over 12 hours. Once this statistical model is trained, it is applied iteratively to predict the evolution of sea-ice thickness, up to a year in advance. Then, we used this deep learning model for variational data assimilation. Data assimilation combines observations and a model to improve forecasts. The use of deep learning techniques in geoscience is a very hot topic right now, and quite new. I started my PhD at the time when everyone was jumping into deep learning to emulate models. The primary goal of my thesis was to determine whether a neural network could even learn a model as complex as neXtSIM. After that, the aim was to evaluate its strengths and limitations. The main advantage is the very low computational cost of the emulator, while the main drawback is that it tends to smooth out sea ice thickness at finer scales.

What was the process for training your neural network, and how did you ensure that the model generalized well beyond the training data?

I trained the neural networks on Jean-Zay, one of the CNRS supercomputers. The most difficult part was selecting what to include in the inputs and outputs, such as additional atmospheric forcings to help the neural network. After that, the training process was fairly standard, and we used a year not included in the training dataset to ensure the neural network didn’t overfit, meaning it didn’t memorize the training data. This approach helps ensure that the model generalizes correctly.

Did you get the results you was expecting ?

I was quite lucky to get good results early on in my PhD, as the emulator was developed after about 18 months. After that, the goal was to develop applications using it and to evaluate the emulator as thoroughly as possible. So, I can say that I achieved the results I was expecting, although we always aim for something better.

What were some of the key insights or surprises you discovered while comparing your deep learning emulator to neXtSIM? Were there any unexpected outcomes?

We were quite impressed by the stability of the emulator. Even though it is trained to predict 12-hour evolutions, it can produce a full-year trajectory that outperforms climatology for up to 6 months. Of course, this stability comes at a cost, which is the smoothness of the field. Nonetheless, the emulator successfully captured the global-scale advection of sea ice and the correct seasonality.

You mentioned that the emulator has a lower computational cost. Have you quantified the savings in computational resources, and how significant are they in practical applications?

No, I haven’t conducted a systematic evaluation of the computational resource savings, and this is not an easy task. The simulations run by Guillaume Boutin were performed on hundreds of CPUs, while I’m working on a single GPU (which, of course, consumes more energy than a single CPU). This presents the first hurdle for comparison. The second challenge is distinguishing between the training phase of the emulator, which took 18 hours for a single run but doesn’t account for all the different experiments conducted, and the inference phase, where the emulator has a very low computational cost. Running a year-long forecast takes less than one minute on an A100 GPU!

As a new postdoctoral researcher, what topic will your research focus on ? What questions will you try to answer ?

The idea is to explore how, and if, emulators of a sea ice model can be integrated into a coupled system. The goal would be to take advantage of the emulator’s low computational cost, which is a major hurdle with complex sea ice models, and see how it interacts with other models, like atmosphere or ocean models.

SASIP integrates both physics and machine learning to develop his new innovative sea ice model. How do these two fields complement each other, and what connections do you see between them in your research?

First of all, we need the physical model to build the machine learning one, as the latter requires a lot of data from the former. It’s essential for deep learning models to take advantage of the latest improvements in the physical model. Deep learning models are extremely efficient in terms of computation, which is probably their biggest advantage. Physical models can also draw inspiration from this. For example, neXtSIM-DG is designed to run on GPUs, with the goal of being parallelizable and as efficient as possible in terms of computational cost, much like deep learning models. We can also mention ideas like model error correction, where a deep learning model is used to correct the physical model, or sub-grid scale parameterization, where a deep learning model represents a physical process more accurately than traditional parameterization, such as Simon Driscoll’s melt pond emulator.

You’ve mentioned several benefits, like computational efficiency and error correction. What do you see as the biggest challenges or limitations when combining physics-based models with machine learning in sea ice modeling?

One common issue with combining deep learning and physics models is the initialization shock. When the physical model takes parameters or states from the machine learning model, there may be significant differences that can lead to instability.

What kind of impact do you hope the project will have ?

I really enjoy the fact that SASIP is working on the development of a new sea ice model using various strategies, particularly the collaborative development of both the physical model and the machine learning approaches that complement it. It might sound a bit cheesy, but I genuinely believe that bringing together people from different fields within this project allows everyone to grow from a scientific perspective. This ensemble of ideas and approaches can only be beneficial for the overall progress of the community. +