-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 4

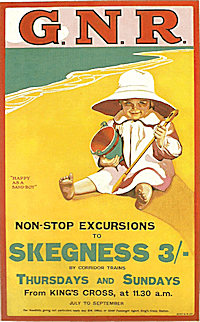

Happy as a sandboy

Q:

From Niki Wessels, South Africa; a related question came from Robert Metcalf in Singapore: Our family recently discussed the expression happy as a sandboy, and wondered where and how it originated. My dictionary informs me that a sandboy is a kind of flea — but why a boy, and why is it happy?

A:

Let me add an explanatory note to your question, as many readers will never have heard this saying. It’s a proverbial expression that suggests blissful contentment:

Made me think it might be a good idea to mark the occasion. Nothing too big, you understand. Not looking for fireworks and flags or anything. I’m a modest man with modest needs. Give me a bit of cake, maybe some tarts, throw in a couple of balloons and I’m happy as a sandboy.

Bristol Evening Post, 11 Aug. 2015.

It’s mostly known in Britain and Commonwealth countries. An older form is as jolly as a sandboy, which is now rarely encountered. The first examples we know about are from London around the start of the nineteenth century.

A sandboy in some countries can indeed be a sort of sand flea, but this isn’t the source of the expression. Incidentally, nor is there a link with the sandman, the personification of tiredness, which came into English in translations of Hans Christian Andersen’s stories several decades after sandboy.

The sandboys of the expression actually sold sand. Boy here was a common term for a male worker of lower class (as in bellboy, cowboy, and stableboy), which comes from an old sense of a servant. It doesn’t imply the sellers were young — most were certainly adults — though one early poetic reference does mention a child:

A poor shoeless Urchin, half starv’d and suntann’d, Pass’d near the Inn-Window, crying — “Buy my fine Sand!”

The Rider, and Sand-Boy in the Hereford Journal, 13 Jul. 1796. The title contains the earliest known reference to a sandboy. The poem was unattributed but is almost certainly by William Meyler of Bath. Note that to be described as suntanned wasn’t then a compliment; it implied an outdoor worker of low class.

The selling of sand wasn’t such a peculiar occupation as you might think, as there was once a substantial need for it. It was used to scour pans and tools and was sprinkled on the floors of butchers’ shops, inns and taprooms to take up spilled liquids. Later in the century it was superseded by sawdust.

Henry Mayhew wrote about the trade in his London Labour and the London Poor in 1861. The sand was dug out from pits on Hampstead Heath and taken down in horse-drawn carts or panniers carried on donkeys to be hawked through the streets. The job was hard work and badly paid. Mayhew records these comments from one of the excavators: “My men work very hard for their money, sir; they are up at 3 o’clock of the morning, and are knocking about the streets, perhaps till 5 or 6 o’clock in the evening”.

Their prime characteristic, it seems, was an inexhaustible desire for beer. Charles Dickens referred to the saying, by then proverbial, in The Old Curiosity Shop in 1841: “The Jolly Sandboys was a small road-side inn of pretty ancient date, with a sign, representing three Sandboys increasing their jollity with as many jugs of ale”. An early writer on slang made the link explicit:

“As jolly as a sand-boy,” designates a merry fellow who has tasted a drop.

Slang: A Dictionary of the Turf, the Ring, the Chase, the Pit, of Bon-tom, and the Varieties of Life, by John Badcock, 1823. To have become an aphorism by this time, sandboy must surely be older than the 1796 poem quoted above.

Quite so. But I suspect that the long hours and hard work involved in carrying and shovelling sand, plus the poor returns, meant that sandboys didn’t have much cause to look happy in the normal run of things, improving only when they’d had a pint or two. Their regular visits to inns and ale-houses presented temptation to a much greater degree than to most people and it has also been suggested that they were often paid partly in beer.

So sandboys were happy because they were drunk.

At first the saying was meant ironically. Only where the trade wasn’t practised — or had died out — could it became an allusion to unalloyed happiness. To judge from the answers to a question about its origin in Notes & Queries in 1866, even by then its origin was obscure.

By 1907, when this railway poster appeared, the small boy on the beach could be humorously described as happy as a sandboy with no hint of the real origin of the expression.